USS Hartford (1858) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Hartford'', a

With the outbreak of the

With the outbreak of the  ''Hartford'' dodged a run by ironclad ram ''Manassas''; then, while attempting to avoid a fireraft, grounded in the swift current near Fort St. Philip. When the burning barge was shoved alongside the flagship, only Farragut's leadership and the training of the crew saved ''Hartford'' from being destroyed by flames which at one point engulfed a large portion of the ship. Meanwhile, the sloop's gunners never slackened the pace at which they fired into the forts. As her firefighters snuffed out the flames, the flagship backed free of the bank.

When Farragut's ships had run the gantlet and passed out of range of the fort's guns, the Confederate River Defense Fleet attempted to stop their progress. In the ensuing melee, they managed to sink converted merchantman , the only Union ship lost during the night.

''Hartford'' dodged a run by ironclad ram ''Manassas''; then, while attempting to avoid a fireraft, grounded in the swift current near Fort St. Philip. When the burning barge was shoved alongside the flagship, only Farragut's leadership and the training of the crew saved ''Hartford'' from being destroyed by flames which at one point engulfed a large portion of the ship. Meanwhile, the sloop's gunners never slackened the pace at which they fired into the forts. As her firefighters snuffed out the flames, the flagship backed free of the bank.

When Farragut's ships had run the gantlet and passed out of range of the fort's guns, the Confederate River Defense Fleet attempted to stop their progress. In the ensuing melee, they managed to sink converted merchantman , the only Union ship lost during the night.

The next day, after silencing Confederate batteries, a few miles below New Orleans, ''Hartford'' and her sister ships anchored off the city early in the afternoon. A handful of ships and men had won a great decisive victory that secured the north, the mouth of the Mississippi river.

Early in May, Farragut ordered several of his ships up stream to clear the river and followed himself in ''Hartford'' on the 7th to join in the conquest of the valley. Defenseless,

The next day, after silencing Confederate batteries, a few miles below New Orleans, ''Hartford'' and her sister ships anchored off the city early in the afternoon. A handful of ships and men had won a great decisive victory that secured the north, the mouth of the Mississippi river.

Early in May, Farragut ordered several of his ships up stream to clear the river and followed himself in ''Hartford'' on the 7th to join in the conquest of the valley. Defenseless,

Again placed out of commission 20 August 1926, ''Hartford'' remained at Charleston until moved to

Again placed out of commission 20 August 1926, ''Hartford'' remained at Charleston until moved to

navsource.org: USS ''Hartford''

(pictures)

hazegray.org: USS ''Hartford''

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hartford Ships of the Union Navy Ships built in Boston Sloops of the United States Navy Gunboats of the United States Navy American Civil War patrol vessels of the United States Hartford, Connecticut 1858 ships Shipwrecks of the Virginia coast Maritime incidents in 1956

sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

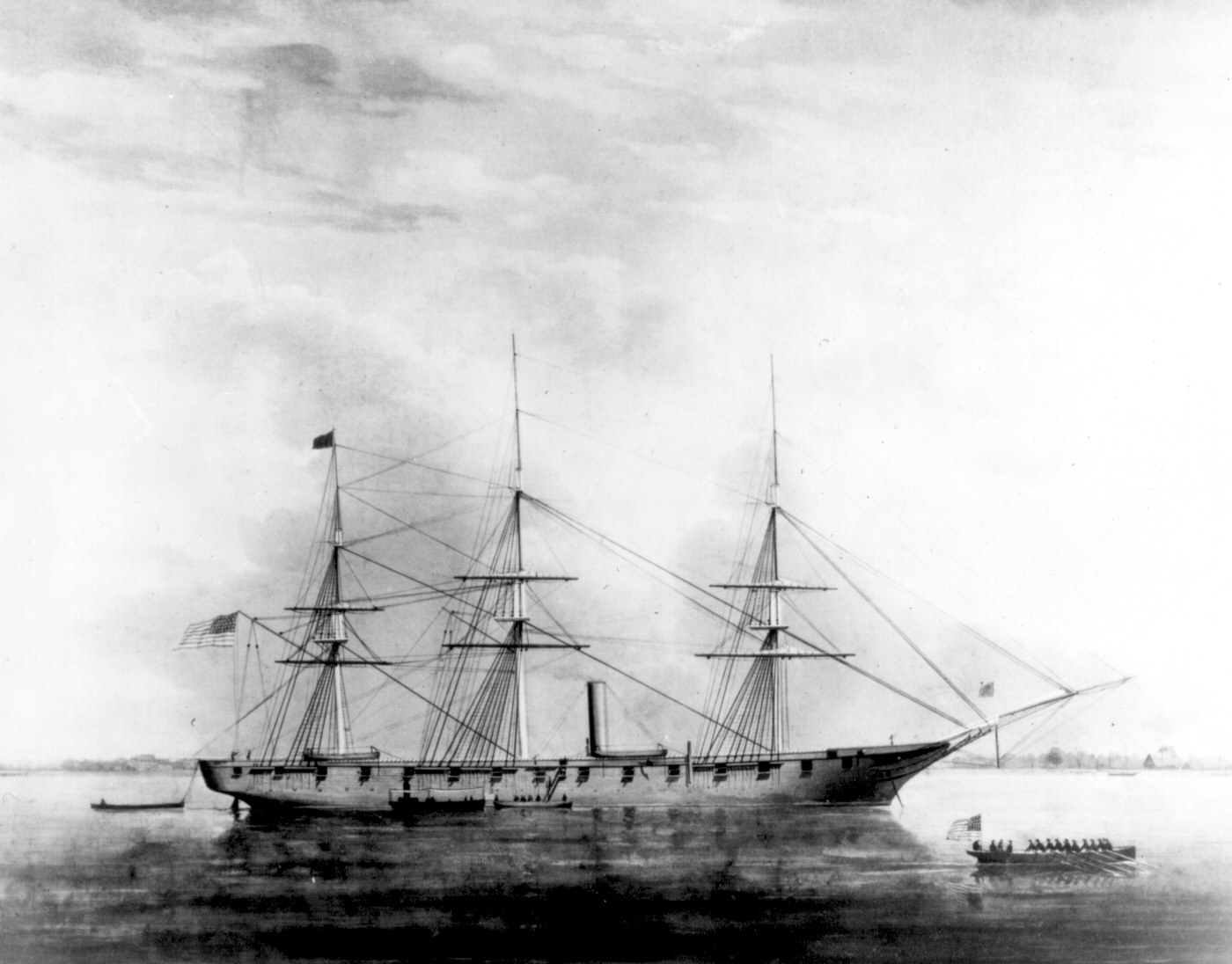

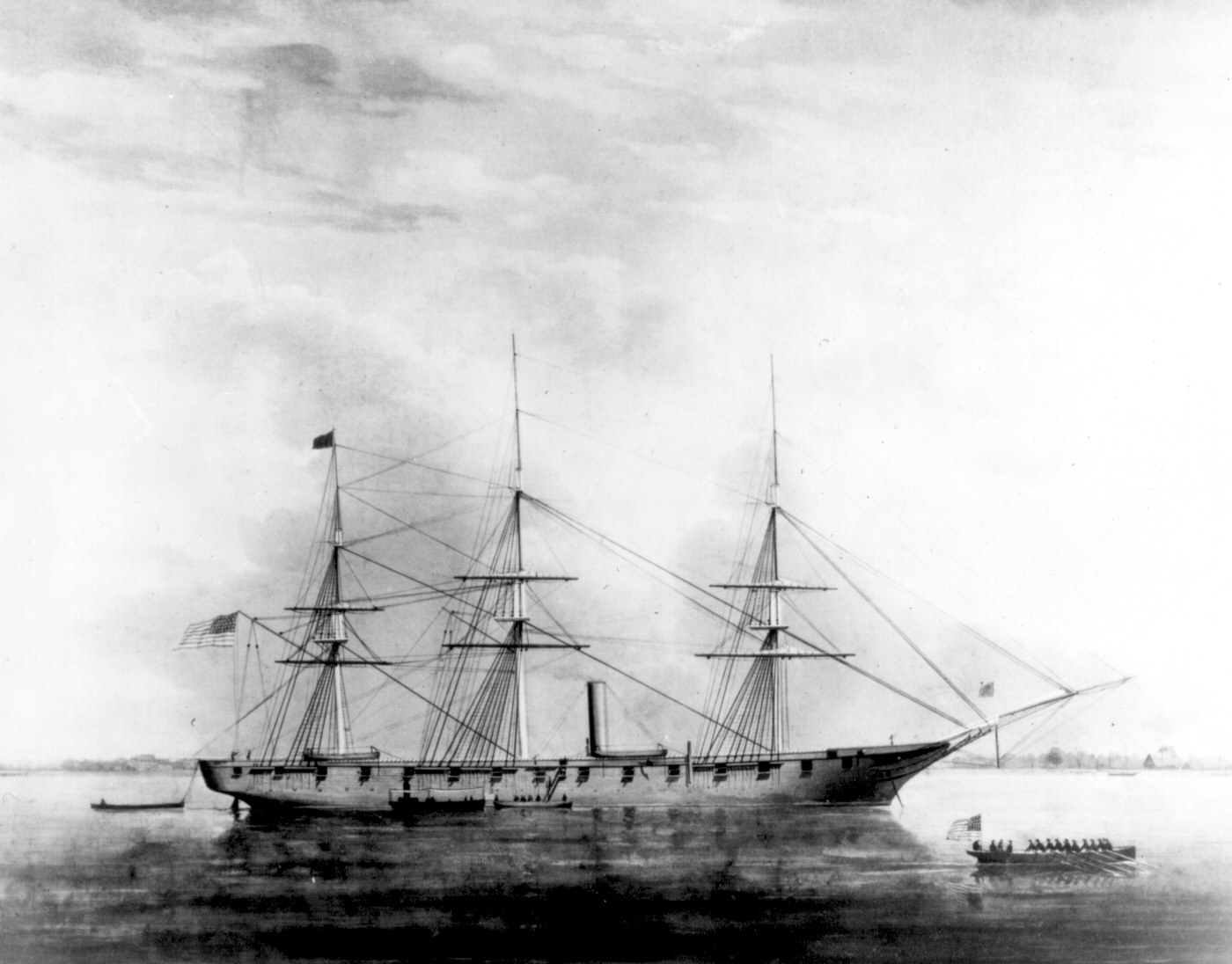

, steamer, was the first ship of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

named for Hartford

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

, the capital of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

. ''Hartford'' served in several prominent campaigns in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

as the flagship of David G. Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. ...

, most notably the Battle of Mobile Bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was a naval and land engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fle ...

in 1864. She survived until 1956, when she sank awaiting restoration at Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

.

Service history

East India Squadron, 1859–1861

''Hartford'' was launched 22 November 1858 at theBoston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

; sponsored by Miss Carrie Downes, Miss Lizzie Stringham, and Lieutenant G. J. H. Preble; and commissioned 27 May 1859, Captain Charles Lowndes in command. After shakedown out of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, the new screw sloop of war, carrying Flag Officer Cornelius K. Stribling, the newly appointed commander of the East India Squadron

The East India Squadron, or East Indies Squadron, was a squadron of American ships which existed in the nineteenth century, it focused on protecting American interests in the Far East while the Pacific Squadron concentrated on the western coast ...

, sailed for the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

and the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. Upon reaching the Orient

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of ''Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the c ...

, ''Hartford'' relieved as flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

. In November she embarked the American Minister to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, John Elliott Ward

John Elliott Ward (October 2, 1814 – November 30, 1902) was an American politician and diplomat.

Biography

John Elliott Ward was born in Sunbury, Georgia on October 2, 1814.

He served as United States Attorney for Georgia, mayor of Savannah, ...

, at Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

and carried him to Canton, Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

, Swatow

Shantou, alternately romanized as Swatow and sometimes known as Santow, is a prefecture-level city on the eastern coast of Guangdong, China, with a total population of 5,502,031 as of the 2020 census (5,391,028 in 2010) and an administrative ...

, Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

, and other Far Eastern ports to settle American claims and to arrange for favorable consideration of the Nation's interests.

Civil War, 1861–1865

With the outbreak of the

With the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, ''Hartford'' was ordered home. She departed the Sunda Strait

The Sunda Strait ( id, Selat Sunda) is the strait between the Indonesian islands of Java island, Java and Sumatra. It connects the Java Sea with the Indian Ocean.

Etymology

The strait takes its name from the Sunda Kingdom, which ruled the weste ...

with on 30 August 1861 and arrived Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

on 2 December to be fitted out for wartime service. She departed the Delaware Capes

Delaware Bay is the estuary outlet of the Delaware River on the northeast seaboard of the United States. It is approximately in area, the bay's freshwater mixes for many miles with the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean.

The bay is bordered inlan ...

on 28 January as flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of Flag Officer David G. Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. ...

, the commander of the newly created West Gulf Blockading Squadron

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederate States of America, Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required ...

. (See also: Confederate blockade mail.)

An even larger purpose than the important blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

of the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

's Gulf Coast lay behind Farragut's assignment. Late in 1861, the Union high command decided to capture New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, the South's richest and most populous city, to begin a drive of sea-based power up the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

to meet the Union Army which was to drive down the Mississippi valley behind a spearhead of armored gunboats. "Other operations," Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

warned Farragut, "must not be allowed to interfere with the great object in view—the certain capture of the city of New Orleans."

''Hartford'' arrived 20 February at Ship Island, Mississippi

Ship Island is a barrier island off the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, one of the Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands. Hurricane Camille split the island into two separate islands (West Ship Island and East Ship Island) in 1969. In early 2019, ...

, midway between Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. The ...

and the mouths of the Mississippi. Several Union ships and a few Army units were already in the vicinity when the squadron's flagship dropped anchor at the advanced staging area for the attack on New Orleans. In ensuing weeks a mighty fleet assembled for the campaign. In mid-March Commander David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter (June 8, 1813 – February 13, 1891) was a United States Navy admiral and a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the U.S. Navy. Promoted as the second U.S. Navy officer ever to attain the rank o ...

's flotilla of mortar schooners arrived towed by steam gunboats.

The next task was to get Farragut's ships across the bar, a constantly shifting mud bank at the mouth of each pass entering the Mississippi. Farragut managed to get all of his ships but across the bar and into the river where Forts St. Philip and Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Qu ...

challenged further advance. A line of hulks connected by strong barrier chains, six ships of the Confederate Navy—including ironclad and unfinished but potentially deadly ironclad , two ships of the Louisiana Navy, a group of converted river steamers called the Confederate River Defense Fleet, and a number of fire rafts also stood between Farragut and the great Southern metropolis.

On 16 April, the Union ships moved up the river to a position below the forts, and David Dixon Porter's gunboats first exchanged fire with the Southern guns. Two days later his mortar schooners opened a heavy barrage which continued for six days. On the 21st, the squadron's Fleet Captain, Henry H. Bell, led a daring expedition up river and, despite a tremendous fire on him, cut the chain across the river. In the early hours of 24 April, a red lantern on ''Hartford''s mizzen peak signaled the fleet to get underway and steam through the breach in the obstructions. As the ships closed the forts their broadsides answered a fire from the Confederate guns. Porter's mortar schooners and gunboats remained at their stations below the southern fortifications covering the movement with rapid fire.

''Hartford'' dodged a run by ironclad ram ''Manassas''; then, while attempting to avoid a fireraft, grounded in the swift current near Fort St. Philip. When the burning barge was shoved alongside the flagship, only Farragut's leadership and the training of the crew saved ''Hartford'' from being destroyed by flames which at one point engulfed a large portion of the ship. Meanwhile, the sloop's gunners never slackened the pace at which they fired into the forts. As her firefighters snuffed out the flames, the flagship backed free of the bank.

When Farragut's ships had run the gantlet and passed out of range of the fort's guns, the Confederate River Defense Fleet attempted to stop their progress. In the ensuing melee, they managed to sink converted merchantman , the only Union ship lost during the night.

''Hartford'' dodged a run by ironclad ram ''Manassas''; then, while attempting to avoid a fireraft, grounded in the swift current near Fort St. Philip. When the burning barge was shoved alongside the flagship, only Farragut's leadership and the training of the crew saved ''Hartford'' from being destroyed by flames which at one point engulfed a large portion of the ship. Meanwhile, the sloop's gunners never slackened the pace at which they fired into the forts. As her firefighters snuffed out the flames, the flagship backed free of the bank.

When Farragut's ships had run the gantlet and passed out of range of the fort's guns, the Confederate River Defense Fleet attempted to stop their progress. In the ensuing melee, they managed to sink converted merchantman , the only Union ship lost during the night.

Battle of New Orleans, 1862

The next day, after silencing Confederate batteries, a few miles below New Orleans, ''Hartford'' and her sister ships anchored off the city early in the afternoon. A handful of ships and men had won a great decisive victory that secured the north, the mouth of the Mississippi river.

Early in May, Farragut ordered several of his ships up stream to clear the river and followed himself in ''Hartford'' on the 7th to join in the conquest of the valley. Defenseless,

The next day, after silencing Confederate batteries, a few miles below New Orleans, ''Hartford'' and her sister ships anchored off the city early in the afternoon. A handful of ships and men had won a great decisive victory that secured the north, the mouth of the Mississippi river.

Early in May, Farragut ordered several of his ships up stream to clear the river and followed himself in ''Hartford'' on the 7th to join in the conquest of the valley. Defenseless, Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-sma ...

and Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

promptly surrendered to the Union ships and no significant opposition was encountered until 18 May when the Confederate commandant at Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

replied to Commander Samuel P. Lee's demand for surrender: "... Mississippians don't know and refuse to learn, how to surrender to an enemy. If Commodore Farragut or Brigadier General Butler can teach them, let them come and try."

When Farragut arrived on the scene a few days later, he learned that heavy Southern guns mounted on the bluff at Vicksburg some above the river could shell his ships while his own guns could not be elevated enough to hit them back. Since sufficient troops were not available to take the fortress by storm, the Flag Officer headed downstream on 27 May leaving gunboats to blockade it from below.

Orders awaited Farragut at New Orleans, where he arrived on 30 May, directing him to open the river and join the Western Flotilla

The Mississippi River Squadron was the Union brown-water naval squadron that operated on the western rivers during the American Civil War. It was initially created as a part of the Union Army, although it was commanded by naval officers, and w ...

and stating that Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

himself had given the task highest priority. The Flag Officer recalled Porter's mortar schooners from Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population within the city limits was 187,041 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, down from 195,111 at the 2010 United States census, 2010 cens ...

and got underway up the Mississippi in ''Hartford'' on 8 June.

Prelude to the Vicksburg Campaign, 1862–1863

The Union Squadron was assembled just below Vicksburg by 26 June 1862. Two days later the Union ships, their own guns blazing at rapid fire and covered by an intense barrage from the mortars, suffered little damage while running past the batteries. Flag Officer Davis, commanding theWestern Flotilla

The Mississippi River Squadron was the Union brown-water naval squadron that operated on the western rivers during the American Civil War. It was initially created as a part of the Union Army, although it was commanded by naval officers, and w ...

, joined Farragut above Vicksburg on the 30th; but again, naval efforts to take Vicksburg were frustrated by a lack of troops. "Ships," Porter commented, "... cannot crawl up hills 300 feet high, and it is that part of Vicksburg which must be taken by the Army." On 22 July, Farragut received orders to return down the river at his discretion and he got underway on 24 July, reached New Orleans in four days, and after a fortnight sailed to Pensacola, Florida

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ...

, for repairs.

The flagship returned to New Orleans on 9 November to prepare for further operations in the unpredictable waters of the Mississippi. The Union Army, ably supported by the Mississippi Squadron

The Mississippi River Squadron was the Union brown-water naval squadron that operated on the western rivers during the American Civil War. It was initially created as a part of the Union Army, although it was commanded by naval officers, and was ...

, was pressing, on Vicksburg from above, and Farragut wanted to assist in the campaign by blockading the mouth of the Red River from which supplies were pouring eastward to the Confederate Army. Meanwhile, the South had been fortifying its defenses along the river and had erected powerful batteries at Port Hudson, Louisiana

Port Hudson is an unincorporated community in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, United States. Located about northwest of Baton Rouge, it is known primarily as the location of an American Civil War battle, the siege of Port Hudson, in 1863.

G ...

.

On the night of 14 March 1863, Farragut in ''Hartford'' and accompanied by six other ships, attempted to run by these batteries. However, they encountered such heavy and accurate fire that only the flagship and , lashed alongside, succeeded in running the gauntlet. Thereafter, ''Hartford'' and her consort patrolled between Port Hudson and Vicksburg denying the Confederacy desperately needed supplies from the West.

Porter's Mississippi Squadron, cloaked by night, dashed downstream past the Vicksburg batteries on 16 April, while General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

marched his troops overland to a new base also below the Southern stronghold. April closed with the Navy ferrying Grant's troops across the river to Bruinsburg whence they encircled Vicksburg and forced the beleaguered fortress to surrender on 4 July.

Battle of Mobile Bay, 1864

With the Mississippi River now opened, Farragut turned his attention toMobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

, a Confederate industrial center still building ships and turning out war supplies. The Battle of Mobile Bay took place on 5 August 1864. Farragut, with ''Hartford'', captained by Percival Drayton

Percival Drayton (August 25, 1812 – August 4, 1865) was a career United States Navy officer. He served in the Brazil Squadron, the Mediterranean Squadron and as a staff officer during the Paraguay Expedition.

During the American Civil War, he ...

, as his flagship, led a fleet consisting of four ironclad monitors

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West Vir ...

and 14 wooden vessels. The Confederate naval force was composed of newly built ram , Admiral Franklin Buchanan

Franklin Buchanan (September 17, 1800 – May 11, 1874) was an officer in the United States Navy who became the only full admiral in the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War. He also commanded the ironclad CSS ''Virginia''.

Early lif ...

's flagship, and gunboats , , and ; and backed by the powerful guns of Forts Morgan and Gaines in the Bay. From the firing of the first gun by Fort Morgan to the raising of the white flag of surrender by ''Tennessee'' little more than three hours elapsed—but three hours of terrific fighting on both sides. The Confederates had only 32 casualties, while the Union forces suffered 335 casualties, including 113 men drowned in when the monitor struck a "torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

" mine and sank.

Twelve of ''Hartford''s sailors were awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. ...

for their actions at the Battle of Mobile Bay. These men were:

* Landsman Wilson Brown

* Ordinary Seaman Bartholomew Diggins

* Coal Heaver Richard D. Dunphy

* Coxswain Thomas Fitzpatrick

* Pilot Martin Freeman

Martin John Christopher Freeman (born 8 September 1971) is an English actor. Among other accolades, he has won an Emmy Award, a BAFTA Award and a Screen Actors Guild Award, and has been nominated for a Golden Globe Award.

Freeman's most no ...

* Coal Heaver James R. Garrison

* Landsman John Lawson

* Captain of the Forecastle John McFarland

* Ordinary Seaman Charles Melville

* Coal Heaver Thomas O'Connell

* Landsman William Pelham

* Shell Man William A. Stanley

Prizes and adjudication

Pacific, 1865–1926

Returning to New York on 13 December, ''Hartford'' decommissioned for repairs a week later. Back in shape in July 1865, she served as flagship of a newly organizedAsiatic Squadron

The Asiatic Squadron was a squadron of United States Navy warships stationed in East Asia during the latter half of the 19th century. It was created in 1868 when the East India Squadron was disbanded. Vessels of the squadron were primarily inv ...

until August 1868 when she returned to New York and decommissioned. Recommissioned 9 October 1872, she resumed Asiatic Station patrol until returning home 19 October 1875. Two of her crewmen, Ordinary Seaman John Costello and Ordinary Seaman Richard Ryan, were awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. ...

for rescuing drowning shipmates in separate 1876 incidents. In 1882, as Captain Stephen B. Luce

Stephen Bleecker Luce (March 25, 1827 – July 28, 1917) was a U.S. Navy admiral. He was the founder and first president of the Naval War College, between 1884 and 1886.

Biography

Born in Albany, New York, to Dr. Vinal Luce and Charlotte Bleecke ...

's flagship of the North Atlantic Station

The North Atlantic Squadron was a section of the United States Navy operating in the North Atlantic. It was renamed as the North Atlantic Fleet in 1902. In 1905 the European and South Atlantic squadrons were abolished and absorbed into the Nort ...

, ''Hartford'' visited the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

, Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, and Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, before arriving San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

on 17 March 1884. She then cruised in the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

until decommissioning 14 January 1887 at Mare Island

Mare Island (Spanish: ''Isla de la Yegua'') is a peninsula in the United States in the city of Vallejo, California, about northeast of San Francisco. The Napa River forms its eastern side as it enters the Carquinez Strait juncture with the eas ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, for apprentice sea-training use.

From 1890 to 1899 ''Hartford'' was laid up at Mare Island, the last five years of which she was being rebuilt. On 2 October 1899, she recommissioned, then transferred to the Atlantic coast to be used for a training and cruise ship for midshipmen until 24 October 1912 when she was transferred to Charleston, for use as a station ship.

Final years, 1926–1956

Again placed out of commission 20 August 1926, ''Hartford'' remained at Charleston until moved to

Again placed out of commission 20 August 1926, ''Hartford'' remained at Charleston until moved to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, on 18 October 1938. President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

wanted to build a naval museum there featuring the ''Hartford'', , and a four-stack destroyer from World War I. When Roosevelt died, plans to establish this museum and to save the ships were abandoned. On 19 October 1945, ''Hartford'' was towed to the Norfolk Navy Yard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility tha ...

and classified as a relic. The ship was allowed to deteriorate, and as a result, ''Hartford'' sank at her berth on 20 November 1956. She proved to be beyond salvage and was subsequently dismantled.

Remains

Major relics from her are at various locations: * Her wheel and fife rail are displayed at theU.S. Navy Museum

The National Museum of the United States Navy, or U.S. Navy Museum for short, is the flagship museum of the United States Navy and is located in the former Breech Mechanism Shop of the old Naval Gun Factory on the grounds of the Washington Navy Y ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

* A rowboat from ''Hartford'' is located at the National Civil War Naval Museum at Port Columbus

The National Civil War Naval Museum, located in Columbus, Georgia, United States, is a facility that features remnants of two Confederate States Navy vessels. It also features uniforms, equipment and weapons used by the United States (Union) N ...

* One of her anchors now sits at the University of Hartford

The University of Hartford (UHart) is a private university in West Hartford, Connecticut. Its main campus extends into neighboring Hartford and Bloomfield. The university attracts students from 48 states and 43 countries. The university and it ...

* Another of her anchors and a cathead

A cathead is a large wooden beam located on either side of the bow of a sailing ship, and angled forward at roughly 45 degrees. The beam is used to support the ship's anchor when raising it (weighing anchor) or lowering it (letting go), and for ...

are on display at Mystic Seaport

Mystic Seaport Museum or Mystic Seaport: The Museum of America and the Sea in Mystic, Connecticut is the largest maritime museum in the United States. It is notable for its collection of sailing ships and boats and for the re-creation of the craf ...

in Mystic, Connecticut

Mystic is a village and census-designated place (CDP) in Groton, Connecticut, Groton and Stonington, Connecticut, United States.

Historically, Mystic was a significant Connecticut seaport with more than 600 ships built over 135 years starting in ...

.

* A third anchor is on display at Fort Gaines (Alabama)

Fort Gaines is a historic fort on Dauphin Island, Alabama, United States. It was named for Edmund Pendleton Gaines. Established in 1821, it is best known for its role in the Battle of Mobile Bay during the American Civil War.

Exhibits include t ...

in Dauphin Island, Alabama, United States.

* One of her Parrott rifle

The Parrott rifle was a type of muzzle-loading rifled artillery weapon used extensively in the American Civil War.

Parrott rifle

The gun was invented by Captain Robert Parker Parrott, a West Point graduate. He was an American soldier and invent ...

s is on display in Freeport, New York

Freeport is a village in the town of Hempstead, in Nassau County, on the South Shore of Long Island, in New York state. The population was 43,713 at the 2010 census, making it the second largest village in New York by population.

A settlemen ...

.

* Two of her Dahlgren smoothbore cannon are on display at Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

in Hartford, Connecticut

* One of her Dahlgren smoothbore cannon is on display in Alden Park at Mare Island Naval Shipyard

The Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINSY) was the first United States Navy base established on the Pacific Ocean. It is located northeast of San Francisco in Vallejo, California. The Napa River goes through the Mare Island Strait and separates th ...

near Vallejo, California

Vallejo ( ; ) is a city in Solano County, California and the second largest city in the North Bay region of the Bay Area. Located on the shores of San Pablo Bay, the city had a population of 126,090 at the 2020 census. Vallejo is home to the ...

* Three Dahlgren cannon on display in Mackinaw City, Michigan

* IX-inch Dahlgren cannon which served on USS ''Hartford'' survive at:"The Big Guns: Civil War Siege, Seacoast, and Naval Cannon". By Edwin Olmstead, Wayne E. Stark & Spencer C. Tucker. Museum Restoration Service, Bloomfield, Canada, 1997.

: Hagerstown, Maryland

Hagerstown is a city in Washington County, Maryland,

United States and the county seat of Washington County. The population of Hagerstown city proper at the 2020 census was 43,527, and the population of the Hagerstown metropolitan area (exten ...

- Tredegar Iron Works

The Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, was the biggest ironworks in the Confederacy during the American Civil War, and a significant factor in the decision to make Richmond its capital.

Tredegar supplied about half the artillery used b ...

registry #117

: Cheboygan, Michigan

Cheboygan ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 4,876. It is the county seat of Cheboygan County.

The name of the city shares the name of the county and probably has its origin from the ...

- Cyrus Alger & Co. #225

: Mare Island, California

Mare Island ( Spanish: ''Isla de la Yegua'') is a peninsula in the United States in the city of Vallejo, California, about northeast of San Francisco. The Napa River forms its eastern side as it enters the Carquinez Strait juncture with the eas ...

- Cyrus Alger & Co. #228

: Vallejo, California

Vallejo ( ; ) is a city in Solano County, California and the second largest city in the North Bay region of the Bay Area. Located on the shores of San Pablo Bay, the city had a population of 126,090 at the 2020 census. Vallejo is home to the ...

- Cyrus Alger & Co. #229

: Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

- Cyrus Alger & Co. #247 & #248

: Petoskey, Michigan- Cyrus Alger & Co. #249

: Gaylord, Michigan

Gaylord is a city in and the county seat of Otsego County in the U.S. state of Michigan. Gaylord had a population of 4,286 at the 2020 census, an increase from 3,645 at the 2010 census.

Gaylord styles itself as an "alpine village" and contain ...

- Cyrus Alger & Co. #250

* Her figurehead

In politics, a figurehead is a person who ''de jure'' (in name or by law) appears to hold an important and often supremely powerful title or office, yet ''de facto'' (in reality) exercises little to no actual power. This usually means that they ...

is displayed in the Connecticut State Capitol

The Connecticut State Capitol is located north of Capitol Avenue and south of Bushnell Park in Hartford, the capital of Connecticut. The building houses the Connecticut General Assembly; the upper house, the State Senate, and lower house, the Ho ...

* Her billethead, trailboards and other items are on display at the Mariners' Museum

The Mariners' Museum and Park is located in Newport News, Virginia, United States. Designated as America’s ''National Maritime Museum'' by Congress, it is one of the largest maritime museums in North America. The Mariners' Museum Library, cont ...

in Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the Uni ...

.

* Her capstan resides in St. Petersburg, Florida at Admiral Farragut Academy

Admiral Farragut Academy, established in 1933, is a private, college-prep school serving students in grades K-12. Farragut is located in St. Petersburg, Florida in Pinellas County and is surrounded by the communities of Treasure Island, Gulf ...

, a college preparatory school named after her captain

* Metal from the propeller of ''Hartford'' was used in the statue of David Farragut at Farragut Square in downtown Washington, D.C.

* Unspecified relic(s) are at the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administrativ ...

* Her ship's bell

A ship's bell is a bell on a ship that is used for the indication of time as well as other traditional functions. The bell itself is usually made of brass or bronze, and normally has the ship's name engraved or cast on it.

Strikes Timing of s ...

can be found on Constitution Plaza

Constitution Plaza is a large commercial mixed-use development in Downtown Hartford, Connecticut.

Construction

Constitution Plaza was built for $42 million and completed in stages from 1961 to 1964.

Its planning and construction were spearheade ...

in Hartford, Connecticut (in front of the Old State House) in the eastern courtyard by the clock tower

* Her hatch cover is used as a coffee table in the Superintendent's office at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland

See also

*Blockade runners of the American Civil War

The blockade runners of the American Civil War were seagoing steam ships that were used to get through the Union blockade that extended some along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coastlines and the lower Mississippi River. The Confederate stat ...

* Bibliography of American Civil War naval history

References

* * Silverstone, Paul H. ''Warships of the Civil War Navies'' Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1989, .External links

navsource.org: USS ''Hartford''

(pictures)

hazegray.org: USS ''Hartford''

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hartford Ships of the Union Navy Ships built in Boston Sloops of the United States Navy Gunboats of the United States Navy American Civil War patrol vessels of the United States Hartford, Connecticut 1858 ships Shipwrecks of the Virginia coast Maritime incidents in 1956